Initial public offerings: Love ’em? Hate ’em? Maybe a little of both?

CNBC can’t make up its mind. It’s doing a decent imitation of Sybil. One day IPOs are the best thing to happen to investors looking to profit from the rising prices of the country’s fastest-growing companies. The next day they’re the unfairest thing. (It should really take a cue from Early Investing, as I’ll explain later.)

This is what it said in early February:

The Wall Street banks that arrange IPOs seem quite confident they can pull off a big 2019, one that will equal or exceed the activity in 2018…

There are 119 companies [set to IPO] that would be classified as “unicorns,” or private companies with valuations over $1 billion. This group includes well-known names like Uber, WeWork and Lyft.

The headline leaves no doubt about how CNBC feels about this: “A giant IPO wave is coming as ‘unicorns’ whet investor appetite.”

But in late March, CNBC published another article on the impending wave of IPOs. This one took a very different approach. The title: “Lyft, Uber and Silicon Valley IPOs help the rich get richer – the losers are public investors.”

It went on to explain that traditional IPOs are dying because “superstar” startups are staying private longer. It compares Amazon going public at $500 million with Facebook going public several years later at $100 billion.

Both companies have experienced tremendous success. But there’s a big difference in how investors have shared that success.

Everyday investors got to benefit from Amazon’s post-IPO growth much more than they did from Facebook’s. Post-IPO investors in Amazon made gains of 1,749,900% (assuming they held on to their shares).

Facebook has a market cap of $475 billion. Not as big as Amazon’s $875 billion, but huge nonetheless. Yet post-IPO investors have made less than 5X.

The article says that the opportunity to ride profits from $1 billion to $100 billion and make 100X is gone.

It explains…

Companies going public this year will do so at much higher valuations, so the chances of massive additional appreciation are lower. This means that private investors are accumulating the majority of the wealth generated from these listings.

CNBC is mostly right. The valuations are ridiculously high. Consider GE Healthcare. Its valuation is $65 billion. WeWork has a $47 billion valuation. Palantir – $41 billion. Airbnb – $31 billion. And the latest reports say Lyft will IPO at a cap of $23 billion.

But higher valuations are nothing new. Companies have been waiting longer to go public ever since the Sarbanes-Oxley Act was passed on July 30, 2002. The act added strict new record-keeping requirements and reforms to securities regulations, which discouraged more private companies from going public.

CNBC should really start reading Early Investing. We’ve been preaching for years that the best way by far to invest in IPO companies is before they IPO, not the day of or the day after.

It’s really the only way for stock investors to capture hypergrowth and mega-profits.

I fully expect Uber to turn into the next Facebook… a company that one day will be worth hundreds of billions while giving post-IPO investors only modest gains. And that’s the best-case scenario.

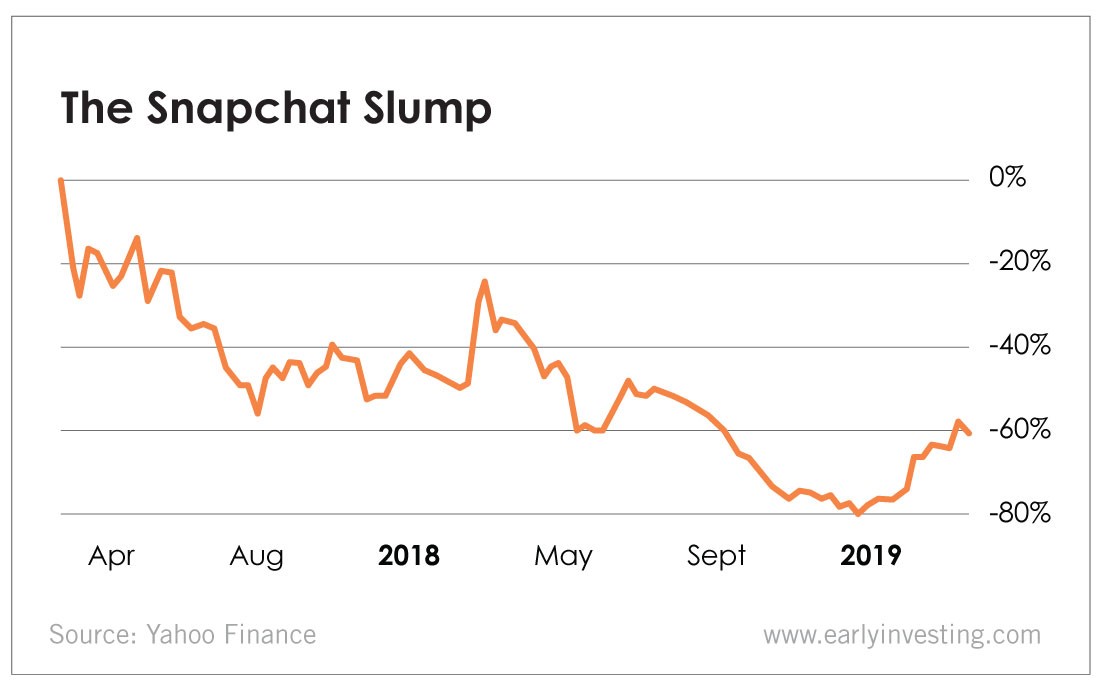

If Uber’s growth fails to live up to expectations, it could become another Snapchat. Take a look…

Snapchat launched its much-hyped IPO at a price of $33 billion two years ago.

It’s since lost about 60% of its value. But a little less than a year prior to its IPO, investors bought shares at a value of $1.8 billion, according to Crunchbase. Despite Snapchat’s precipitous fall, those investors have still made 8X.

Let me repeat: IPO investors have lost about 60%. Pre-IPO investors are up 700%.

Pre-IPO investors – whether they’re investing in Uber or other big IPOs – don’t typically worry about losses. Their only concern is big upside.

We make investment recommendations of early-stage companies with valuations ranging from $5 million to $30 million. We don’t ride companies going from a $1 billion to a $100 billion market cap. Instead, our 100X gains come from companies going from $5 million to $500 million.

We also welcome companies going from $20 million to $200 million for 10X gains. Unicorns are the gravy in our investing model, and decacorns (companies with a valuation of $10 billion or more) are outliers. We don’t spend any time thinking about them.

These are the kinds of gains that IPOs can no longer provide. Perversely, the bigger the IPO, the bigger the headlines and excitement, but the smaller your financial reward. My back-of-the-envelope math has Uber’s stock already absorbing 80% of its total growth trajectory, Lyft’s 70% and Slack’s 60%.

CNBC finally seems to get it. But when we get close to Uber’s IPO, I guarantee it’ll be writing those breathless articles along with the rest of the mainstream media.

But take it from me: Big IPOs aren’t your friend.