In baseball, failure is richly rewarded. One of my favorite players, Jackie Bradley Jr. (JBJ), plays center field for the defending World Series champions, the Boston Red Sox. He’s currently hitting .149. And he’s paid $8.55 million a year. (Maybe that’s why baseball is called “the beautiful game.”)

In startup investing, failure is also richly rewarded. CB Insights tracked more than 1,100 tech companies raising seed rounds from 2008 to 2010. Only 10.2% had exits of $50 million or more. And only 1% became unicorns. Yet scores of investors became rich investing this way. (Which is why I believe startup investing is “the beautiful game.”)

Nightmare or Dream Come True?

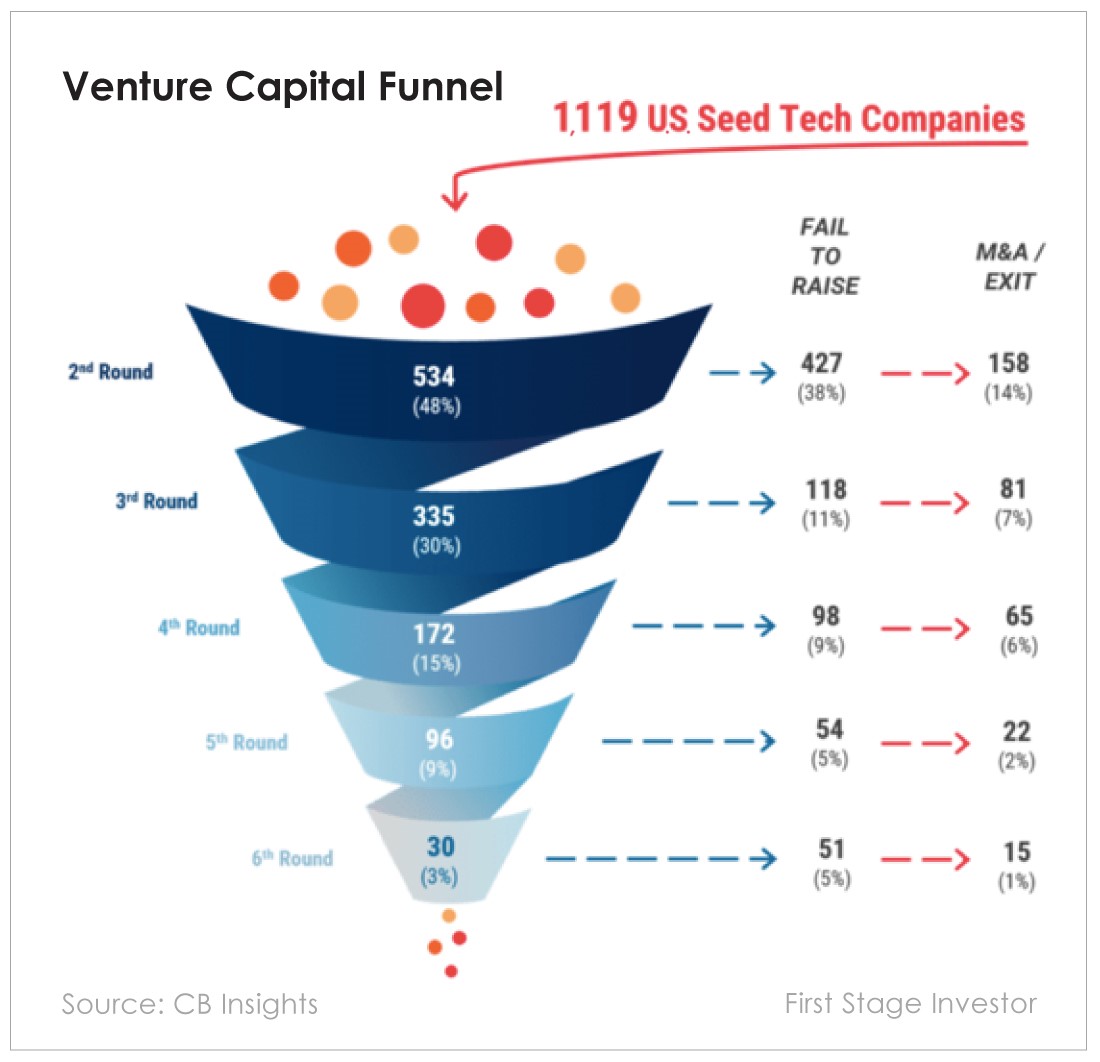

Failure and wealth walking hand in hand seems downright un-American. It’s certainly not an easy thing to grasp, which is why this funnel is my go-to “inkblot.”

Here’s what most people see: Fewer than half the startups that raise a seed round make it to the next round. A mere 9% reach Series D (the fifth round), where late-stage liquidity events begin. Only 3% reach the sixth round. And only 1% become unicorns.

Here’s what early investors see: More than 300 companies achieve an exit or a merger and acquisition. That’s a pretty good-looking chart with a .304 batting average (much like in baseball, a 30% success rate is pretty good). I suspect JBJ would hand over his first born to hit more than .300.

Improving the Odds

I’ve known about this funnel for years. But looking at it again with fresh eyes, there are some takeaways that you need to know about…

The funnel shows that the biggest drop-off happens during a startup’s seed stage. There’s a lot of risk here. More than half of seed companies fail to reach a second round. And many of those that fail to raise again go out of business.

This immediate drop-off scares some investors. If they have a less than 50% chance of choosing companies that make it to the next round, how much slimmer are their chances of picking big winners?

That’s not how I see it. I like to focus on 12 to 15 month plans for seed-stage companies. I want to see if their goals are realistic and achievable. And, if so, whether they’re ambitious enough to attract investors in the next round of fundraising. It’s easier to evaluate the probability of a 12-month outcome than, say, a 12-year outcome. And once companies reach the next round, the success rates increase. And the potential returns are significant.

From the same group of companies this funnel is based on, 74, or 6.6%, had exits of $100 million or more, including five unicorns. More than 10% had exits of $50 million or more.

Most seed companies carry a valuation of anywhere from $5 million to $15 million. So taking the median of $10 million, seed investors made 5X to 100X from this group. Investors who got into the 43 companies that had exits of $200 million and up pocketed gains starting at 20X.

Still not great odds, you say? I beg to differ. After looking at thousands of seed companies over the past five years, I can say half the companies that receive seed money don’t deserve it. Serious investors should be able to reduce the original 1,119 startups by half, at the very least. (I’m being ultra-conservative. I’d have no trouble cutting it in half again.)

If you invested in just one of these 560 companies (we’ve cut the group by half, remember?), you have a 13.2% shot at 10X to 100X gains. But if you invested in 10 of these companies, the probability is extremely high that you’d land one or two winners, perhaps including one of the 25 exiting at $200 million (20Xers) or one of the 13 exiting at $500 million (50Xers).

It’s also important to keep in mind that not all companies in the “fail to raise” category are losers. Many don’t raise again because they’ve become profitable and don’t need the money. Some are generating a few million dollars in revenue per year and could well become prime mergers and acquisitions targets at some point. These companies could give investors anywhere from 50% losses to 100% gains.

Once again, I’m struck by how different it is for us retail investors than it is for venture capitalists (VCs). They need the really big winners – $500 million exits at the very least. And they’re increasingly dependent on the unicorn exits. VCs are writing bigger and bigger checks and need bigger and bigger winners to offset the losers.

Retail investors can profit from smaller investments – and smaller exits. That’s a huge advantage.

The Funnel Speaks

This funnel tells me to choose companies with big plans in the long term and realistic plans in the short term, and to choose founders who have the execution chops to achieve both.

And when the funnel speaks, I listen.

Good investing,

Andy Gordon

Co-Founder, First Stage Investor